To the uninitiated, film sets are controlled, polished environments where visual details fall neatly into place. Award-winning makeup artist Udu Alakpa says the reality is far messier. Long hours, unpredictable weather, shifting schedules, and last-minute changes mean that every department is constantly adapting just to keep production moving.

Makeup and hair, often mistaken for finishing touches, are among the departments most exposed to this instability.

Udu Alakpa has worked across film and television, including Niyi Akinmolayan’s ‘Colours of Fire’, Daniel Etim Effiong’s ‘The Herd’, ‘All the Colours of the World Are Between White and Black’, ‘Reel Love’, and Nigeria’s first Cannes selection, ‘My Father’s Shadow’. Her experience offers a rare window into how Nollywood’s makeup and hair departments hold productions together.

It helps manage continuity, supports performance, and protects the credibility of a film’s world when conditions refuse to cooperate.

Alakpa did not enter filmmaking through a traditional arts pipeline. Her first exposure to a professional film set came through makeup artist Feyisayo Oyebisi, widely known as Feyzo, while studying statistics at the Federal School of Statistics, Ibadan. From that early experience, she absorbed the discipline behind the craft: preparation, restraint, and a clear understanding that makeup exists in service of story rather than personal expression.

But long before that, she had been sketching faces and her early exposure to visual fundamentals of light, shade, balance, and dimension became the backbone of her approach to makeup.

On film sets, those principles matter more than trends. Alakpa explains that many makeup artists struggle in production environments because they repeat the same look across different faces. Film, however, demands the opposite. Every face has its own structure and every character has its own visual priorities. Makeup, in her view, is not about hiding flaws but about directing attention by making certain features recede and others emerge depending on what the story needs.

This way of thinking becomes essential when conditions change unexpectedly. If an actor arrives with altered hair, reshaped brows, or a look that contradicts continuity, technical knowledge alone is not enough. The artist has to think fast under pressure, observe before acting, listen to directors and actors, and adjust without ego when plans fall apart.

‘The Herd’ was one of the projects that pushed Udu’s creativity. After receiving the script, Alakpa broke it down character by character, creating lookbooks that mapped injuries, mutilations, and physical deterioration across the story.

However, the film was shot during the rainy season, which required constant adjustments to workflow and timing. Makeup and special-effects processes often had to pause and restart as weather conditions changed, with materials packed away and reset once filming resumed.

In addition to the weather, shooting in the bush in Abeokuta came with its realities, affecting how work could be prepared and maintained. With no proper hiding places and little opportunity for rest between setups, the work demanded efficiency, foresight, and adaptability. Looks had to be designed to hold under environmental stress while remaining consistent on camera, requiring practical decisions that balanced realism, durability, and speed.

It was not an ideal setup, but the film demanded solutions rather than complaints. The result was a film whose violence and its aftermath felt grounded rather than theatrical.

‘Adaptability is a survival skill on set,’ says Udu Alakpa

Adaptability, Alakpa says, is the defining requirement for anyone hoping to last on film sets. Productions rarely unfold exactly as planned. Actors cut or dye their hair for other projects, arrive with unexpected changes, or present constraints that were never discussed in pre‑production. Continuity becomes a daily negotiation.

In one instance, an actor arrived on set with freshly cut and dyed hair despite previously appearing with dreadlocks. Re‑creating the original look required immediate decisions: sourcing matching hair, adjusting length, rebuilding texture, and restoring continuity without halting production. These are the moments, Alakpa says, when preparation and clear thinking matter more than perfection.

Equally important is understanding how actor comfort shapes the work. A look that disrupts performance, even if it aligns with a director’s initial vision, ultimately weakens the film.

Udu Alakpa prioritises early conversations with actors, sharing visual plans and finding compromises that protect both character integrity and on-screen presence. Film makeup, she argues, succeeds only when it disappears into performance

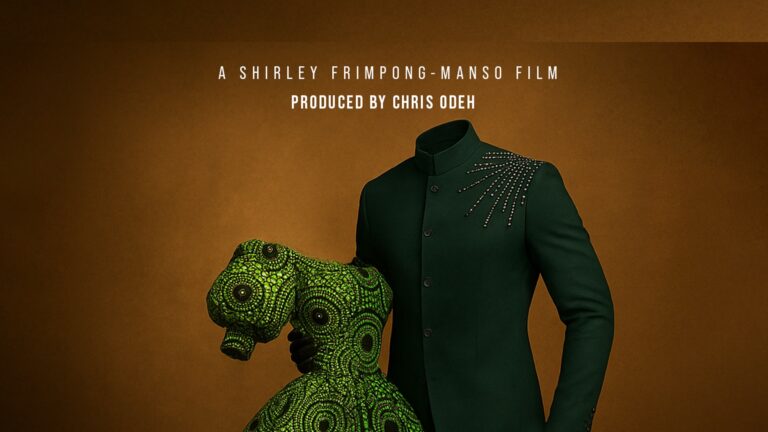

If ‘The Herd’ tested endurance, ‘Colours of Fire’ demanded restraint. Designed as a historical‑leaning epic, the film required hair and makeup choices that avoided contemporary giveaways while still accommodating modern production realities.

Director Niyi Akinmolayan came into pre‑production with clear visual references for each character. Alakpa and her collaborators responded with practical interpretations based on feasibility, budget, and actor needs.

One challenge involved modern tattoos that could not realistically exist in the film’s world. Rather than covering them daily, Alakpa reworked a prominent tattoo on Uzor Arukwe’s arm into a character‑specific symbol that aligned with the story’s internal logic.

Hair decisions followed similar logic. Frontals and visibly modern wig constructions were avoided as much as possible, working within those limits to disguise lace, control texture, and maintain period credibility.

These decisions were rarely visible to audiences, but they shaped how believable the film’s world ultimately felt.

Recognition for this kind of work is rare, which is why Alakpa describes winning the Achievement in Makeup award at the 2025 Reffa Awards in Ghana for ‘My Mother Is a Witch’ as unexpectedly emotional. The film, directed by Niyi Akinmolayan, earned her first major industry award, affirming years of labour that often goes unnoticed beyond the set.

She recalls thinking less about personal achievement and more about the people who shaped her—the mentor who trained her, the teams who supported her, and the productions that demanded more than she thought she could give.

Despite that moment, Alakpa resists framing awards as turning points. For her, the work remains collaborative and largely invisible. Makeup and hair do not function in isolation; they intersect constantly with costume, lighting, and production design. When these departments align, the work disappears into the film, allowing audiences to believe in the characters without noticing the effort behind them.

In an industry where technical departments are frequently under-resourced and overlooked, Udu Alakpa’s experience underscores a simple truth of filmmaking: without makeup, hair, and the improvisation that sustains them, many film productions would quite literally fall apart.

‘Colours of Fire’ is now showing in cinemas and ‘The Herd’ continues streaming on Netflix.