Last weekend, Kava, a streaming platform born from the collaboration of Filmhouse and Inkblot, launched. It joins the other homegrown streamers—Circuits, Showmax, Ebonylife Plus, and Iroko TV—trying to fix the distribution crisis plaguing Nollywood. But the announcement was met with scepticism from Nollyphiles.

For Vanessa Ohaha, a fashion and culture journalist, she fears an oversaturation is at hand which will harm the ecosystem as the purchasing power of Nigerians keeps dwindling. “I thought it was hilarious that their first solution to Nollywood’s distribution problem was not collaboration but an oversaturation,” she expresses concern. IkeGod, a popular book and movie reviewer, holds the same thoughts as Ohaha: “I wish it was just one streaming service rather than a lot.”

This scepticism is not only hinged on a desire for more streaming collaborations. There is a certain distrust that the Nollywood audience nurses. It is not the first time a local streamer has launched and promised to blaze the trails. There is a déjà vu element to it—not the good kind. In terms of quality, the industry has failed to meet audience expectations and with the exit of the streaming giants—Netflix and Prime Video—that distrust has only grown.

While there are valid concerns surrounding the offshoots of these streamers, our collective cynicism may blind us to the few advantages the streaming wars might provide the industry. One of these benefits is healthy competition.

Historically, streamers like Iroko had no real competition at the time it launched and that may have stunted its growth. Healthy competition urges markets to stay on their toes. Thus, the streaming scramble could force streamers to invest in quality over quantity—which is what Nollywood is most associated with. They need to justify subscriptions; give subscribers reasons to seek and pay for their services. The ripple effect is an increase in quality of production because audiences won’t repeatedly pay for low value. And the probability of global streamers taking a second glance at Nollywood.

Platforms like Netflix and Prime Video made big early moves in Nollywood when they first arrived with commissioned projects like ‘Far From Home’ and ‘She Must Be Obeyed’ but momentum has slowed and streamers like Prime Video have exited the landscape. The advent of local competitors like Kava, Circuits and so on generates pressure. To retain their market share, the global streamers might reinvest in local originals, increase marketing spend in Nigeria or, better still, pay more for licensing films and series.

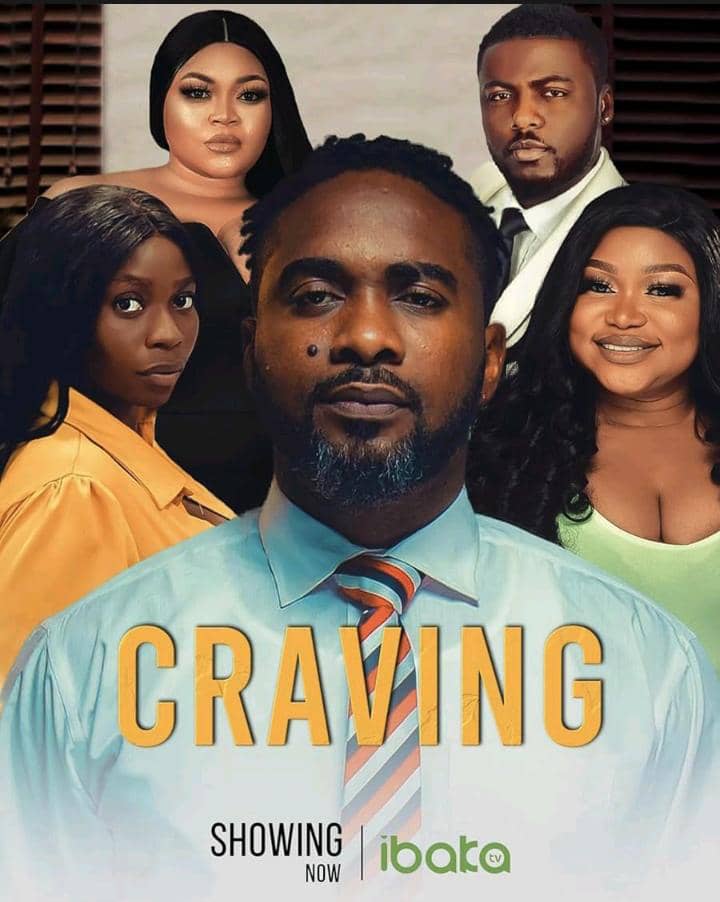

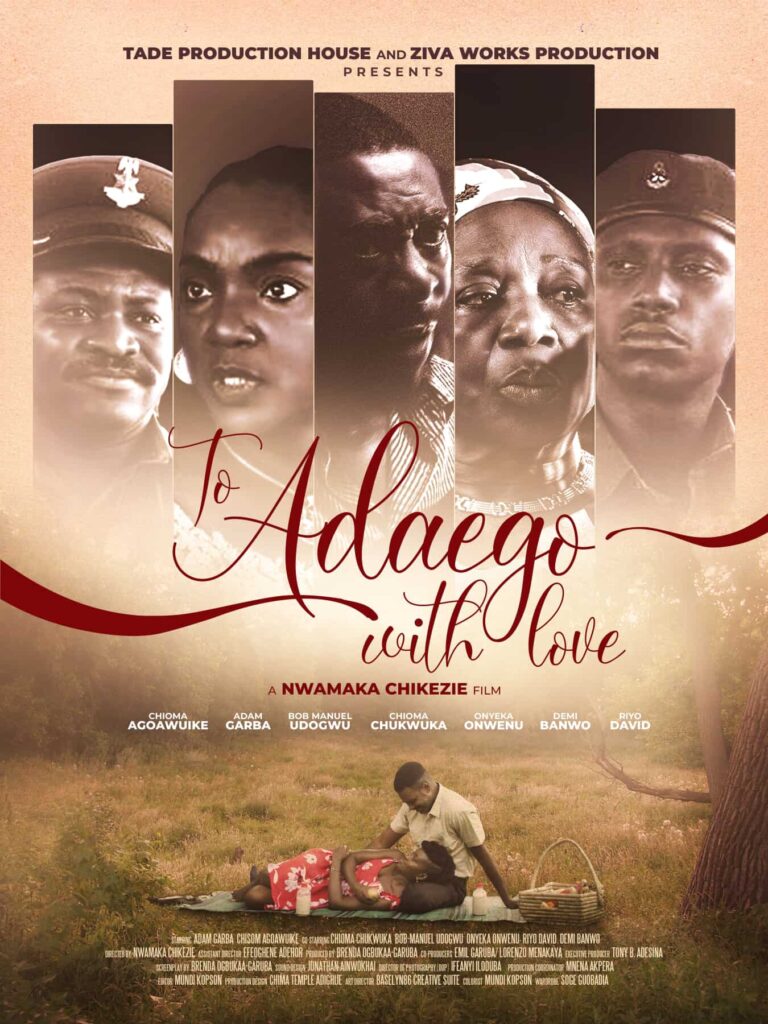

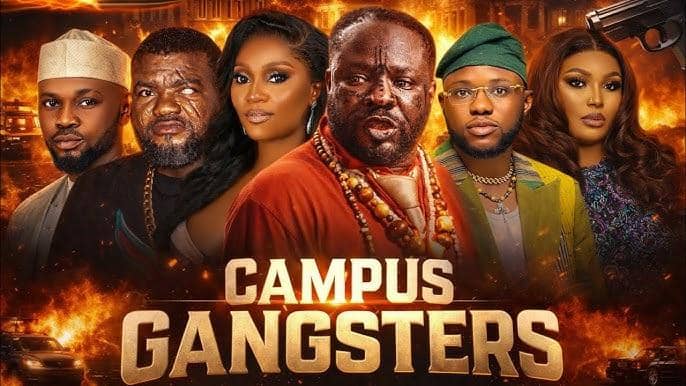

It is also important to note that these local streamers are striving to fix one of the industry’s banes: distribution. Many Nollywood and African titles struggle to find a home after their theatrical or Netflix runs. For instance, in August about sixteen titles are set to exit Netflix and without a proper distribution channel, they get lost forever or end up on YouTube. And the fundamental problem with YouTube is the restriction of IP monetisation and the film’s long-term potential.

Uploading a film on YouTube is often the final stop for that IP. Once a film is free, it is almost impossible to charge for it elsewhere; it loses its premium status. However, with a controlled and paid platform, you can sell the same IP multiple times. Theatrical releases give you ticket sales, streaming deals provide you subscription or licence fees for different territories and with television rights you get syndication or pay-tv packages.

A perfect embodiment is Funke Akindele’s ‘Jenifa’s Diary’. It started out as a small TV series, captivated the hearts of many, and then turned into a cinema film (‘Everybody Loves Jenifa’) that made a splash at the box office and still has value for re-release or licensing. An industry with a competitive streaming culture means more Nigerian filmmakers get to keep the larger control of their IP.

An industry void of a viable distribution channel will be dependent on foreign streamers’ commissions and decisions. The rise of these streamers puts filmmakers in the driver seats of their stories. They gain more control within the movie framework. And with the increase in local streamers, there is an opportunity to resuscitate abandoned projects like ‘Blood Sisters’, ‘Far From Home’ and breathe life into TV pilots and drafts lying in screenwriting softwares.

If the streaming war heats up, more money flows into the content, creating more jobs and better stories for the industry. It is indeed true that this new development stands the risk of an oversaturation, but more platforms also mean more competition, more marketing, and more audience growth.

The real danger is if we allow our very valid scepticism to hinder us from testing out these platforms, causing them to die before they can even sprout. While it may be hard, it will serve both filmmakers and audiences to lean more towards curiosity than cynicism, and maybe just maybe this won’t be another failed industry attempt.