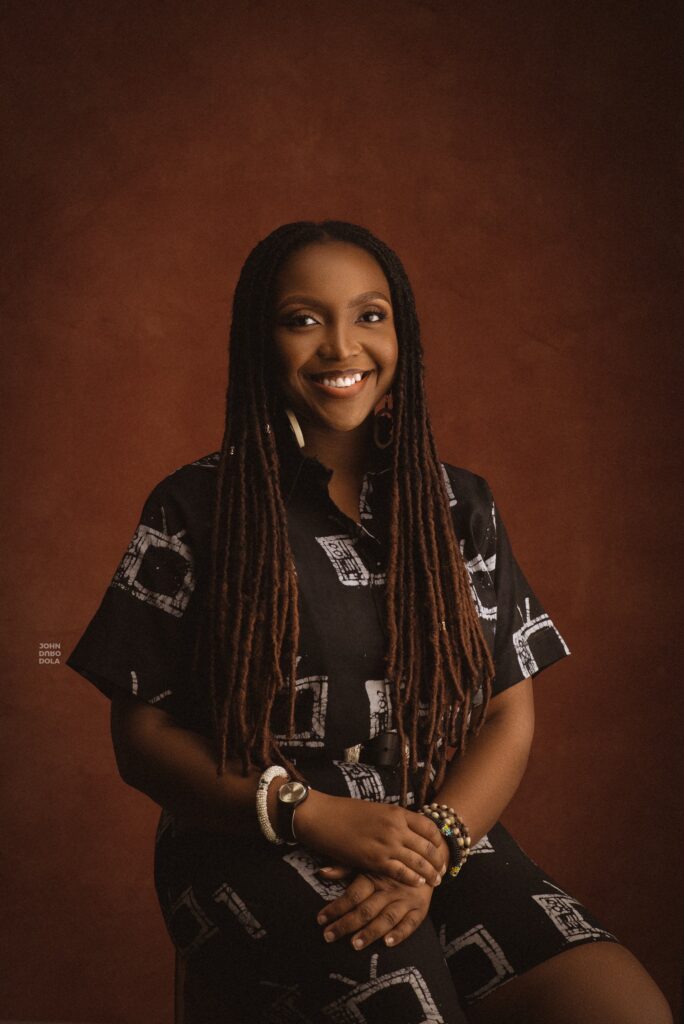

In ‘Colour Me True’, writer–director Toluwani Obayan Osibe turns her attention to a question that has lingered across much of her life: what does it mean to come home? Not the sentimental or nostalgic idea of home, but the version that is tied to identity, memory, survival, and the places we return to when the stories we tell about ourselves begin to unravel.

The film, the 10th title from Native Filmworks and Michelangelo Productions’ First Features Project, follows Sylvia Philips, a polished reality TV star whose public life collapses when the truth about her origins surfaces. Exposed and unmoored, Sylvia is forced to return to the orphanage she once fled, along with the sister and community she abandoned in the process. There, she must confront the girl she used to be, the shame she tried to outrun, and the comfort she didn’t think she deserved.

Starring Shalewa Ashafa, Eseosa Bernard, Nnamdi Agbo, and Bucci Franklin, the film moves gently through themes of identity, belonging, and the difficult work of self-confrontation. Osibe, who both co-wrote and directed the feature, approached the project with a familiarity that comes from living inside the story long before stepping onto set. The dual role allowed her to move between the emotional and the practical—rewriting in real time, working closely with the actors, and protecting certain story beats she felt were essential to the film’s inner logic.

What emerges is a narrative shaped by her own evolving understanding of home: not a place one returns to unchanged, but a place that insists on honesty. In our conversation, Toluwani Obayan reflects on the internal questions that guide her filmmaking, the pressures of performance—public and private—and what she hopes young women take from Sylvia’s journey back to herself.

You’ve always gravitated toward intimate, human-centred stories; ‘This Lady Called Life’ explored Aiye’s emotional journey, and now Colour Me True’ follows Sylvia’s reckoning with self. What draws you to these deeply personal narratives?

I’ve always believed we underestimate the importance of what’s happening inside us. A lot of what we celebrate—success, beauty, charisma, confidence—starts internally, but we rarely give attention to that internal landscape. We tend to measure a person’s life from the outside: their clothes, their career, their money, their posture. But I’ve come to learn that you can have the perfect exterior and still be in deep turmoil.

People suffer silently because the inside hasn’t been tended to. So I’m drawn to stories that allow people to confront that inner world—stories that say, “Let’s deal with the roots, not the leaves.”

And maybe it’s because I’ve had to do that work myself. I’ve had seasons where I had to face the truth of who I was and who I wasn’t. Telling these stories is my way of helping others do the same.

In ‘Colour Me True’, Sylvia’s carefully crafted public identity collapses. Why were you interested in exploring the tension between who we are privately and who the world expects us to be?

It came from my own life. I grew up in a spotlight I never asked for; my mom worked in university management, and because I look so much like her, everyone knew me. Perfection felt compulsory. I didn’t think I was performing; I thought I was being myself. But later, especially after losing both my parents within a short period, my whole world unravelled, and suddenly I couldn’t maintain that façade.

People didn’t always understand the shift; it cost me relationships. But that unravelling was also freedom. For the first time, I learnt what it felt like to be true, even if the truth was messy.

And when you look around, especially in celebrity culture, you see how much pressure people are under. One scandal, one misstep, and their entire identity crumbles. The public demands perfection, but perfection is impossible. We never leave room for people to be fully human.

That contradiction, the public’s hunger for authenticity but simultaneous punishment of it is something I really wanted to explore with Sylvia’s character.

Reconnection—especially with one’s past—is a key thread in the film. What inspired you to root Sylvia’s transformation in a return to the orphanage and the girl she once was?

I once visited an orphanage, and what struck me wasn’t the younger children; they were joyful, hopeful, and excited to play and receive gifts. It was the teenagers. They stayed in their rooms, indifferent. It felt like they’d been disappointed too many times. They had seen people come and go and forget them. It broke something in me.

I wanted Sylvia’s pain to be real, not symbolic. I needed a wound deep enough that reinvention would feel like survival. An orphanage carries a certain emotional truth: a longing for belonging, the fear of abandonment and the ache of being unwanted.

I wanted the audience to understand why she ran and why running came at a cost. Returning there forces her to face that original wound but also to rediscover the people who loved her long before she learnt to perform.

The film frames reconnection not as reconciliation with pain, but as confronting the parts of ourselves we’ve rejected. How did you shape Sylvia’s journey toward accepting Ivie, the girl she once was?

I wanted the transformation to feel real. In life, we rarely have one thunderbolt moment of change. It’s gradual. It happens in subtle shifts, in small acts, in quiet realisations.

So we built her evolution into everything: her hair, her makeup, her clothing and her posture. She starts the film looking slightly synthetic and overly styled; as the story unfolds, she becomes more natural, stripped down and softer. Not because she’s becoming someone new, but because she’s returning to someone true.

Emotionally, the key to her transformation is love. Being around people who truly know her—and still choose her—creates an environment where truth becomes safe again. And the conflict comes from the other character who keeps pulling her back into performance. It’s a tension many of us know too well.

Ultimately, her acceptance comes from realising that what she thought was weakness was actually the foundation of who she is.

Themes of home and belonging run subtly through the story, not in a nostalgic way, but in a “what does home demand of you?” way. What were you trying to say about the idea of home in this film?

Home is where you have a place, no matter what. After my parents died, my brother and I had to leave the place we’d always called home. We weren’t children, but I often think of children who go through that instability with no support. I spent years feeling like I was floating, like there was nowhere I could be unfiltered, unpolished, imperfect, and still loved.

Home is the place where you can be tired without being judged. Where you’re allowed to be wrong sometimes, because whoever you are, you still belong. You don’t earn home. Home simply is.

For Sylvia, everything she built was fragile; one truth destroyed it. But the place she ran from, that she was ashamed of, was the place still standing. The people there didn’t demand performance. They demanded honesty. That’s home.

Identity plays a huge role here, especially the gap between Sylvia’s public persona and her real origins as Ivie. What real-life pressures or observations informed your understanding of how women in the public eye manage identity?

Women in the public eye face an intense, almost inhumane pressure to be perfect. I recently saw a post comparing Sarah Jessica Parker at the height of Sex and the City to now, as though ageing is a moral failure. No other profession punishes ageing this brutally.

Beyond ageing, there’s the expectation to be polished, polite, composed and desirable but not too desirable. Visible, but not too visible. Authentic, but not too authentic. It’s exhausting.

While people say they want “realness”, they also mock and punish celebrities when they’re real. So the public often demands the very performance they criticise.

That contradiction informed Sylvia’s struggle. She’s not just performing for fame; she’s performing because the world rewards performance and punishes vulnerability.

A core emotional arc is the relationship between Sylvia and her sister, Ruth. What did sisterhood represent for you in this story, and how did you want their dynamic to shape Sylvia’s transformation?

I wanted their relationship to echo the story of the prodigal son, not in a moralistic way, but in the sense of two very different responses to the same pain.

Ruth stays. She nurtures. She pours herself into the home, into the children, into beauty. Every wall you see in Little Homes carries her artistic touch. She could be more and go further, but she chooses to heal inwardly.

Ivie leaves. She runs. Reinvents. Performs. And while her path looks more glamorous, it’s rooted in pain. I wanted their relationship to be symbiotic. Ruth grounds Sylvia in truth. Sylvia pushes Ruth out of her comfort zone. They both need each other to become whole.

Through them, we see that home is not just a place; it’s people who hold your story with tenderness.

What do you ultimately hope audiences—especially young women watching Sylvia grapple with truth, image, and belonging—carry with them after experiencing ‘Colour Me True’?

I hope they come home to themselves. I hope they stop looking for love in places that demand performance. I hope they embrace truth even if it’s imperfect, even if it’s uncomfortable, because truth is safe, grounding, and beautiful.

You don’t have to invent a new self to be worthy. You don’t have to shrink to be loved. My hope is that young women walk away feeling permission to be honest, to be flawed, to be human and to belong anyway.