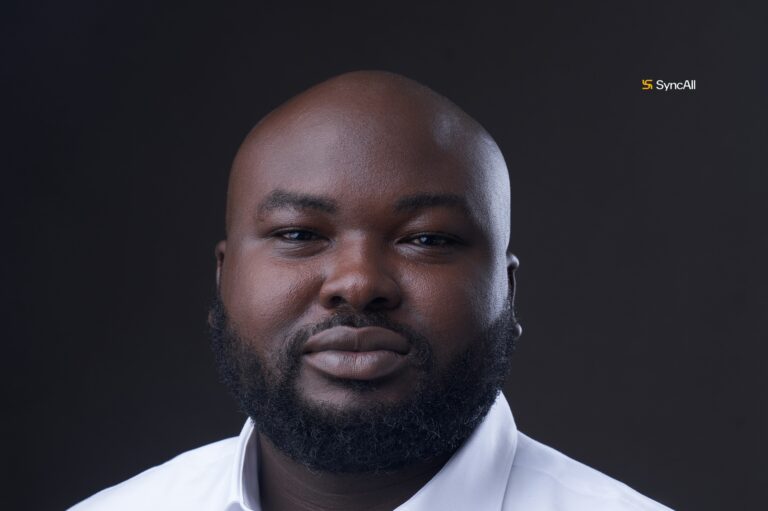

When Adeoye Adetunji talks about his process, it’s less craft and more calling. The award-winning animator behind ‘Pa Aromire’ doesn’t just create stop-motion films; he channels them. What begins as a vision during meditation unfolds into weeks, months, or sometimes years of solitary world-building. On his dining table, with a phone, handmade puppets, and an unwavering sense of purpose, Adeoye constructs sacred spaces frame by frame.

His journey into stop motion began during the isolation of the pandemic. With no actors, no locations, and no crews, he was forced to confront a central question: how do you tell stories when you’re entirely alone? What started as a practical workaround soon revealed itself as something deeper. In the solitude, he discovered a kind of creative freedom and a sense of purpose. Stop motion didn’t feel like a compromise; it felt like a calling. From the moment he started building those miniature worlds, he knew he had found his form.

The first act of surrender became ‘Pa Aromire,’ inspired by Yoruba mythology and spiritual symbolism, and became the first animated film to win an AMVCA. But for Adeoye, the work isn’t about accolades or attention; it’s about obedience to something higher. In a cinematic culture obsessed with scale, speed, and visibility, he moves in the opposite direction: slowly, deliberately, invisibly.

In this Off Camera conversation, Adeoye opens up about building universes from scratch, navigating artistic isolation, and why he doesn’t worry about audience approval. He reflects on the divine nudges that shape his work, the rig he built to shoot a rotating wisdom tree, and the difference between posting for validation and posting from purpose.

Your stop-motion film ‘Pa Aromire’ stood out for its Yoruba myth-inspired storytelling. What does it mean to reinterpret cultural history through such a slow, meticulous form like stop motion and what were you hoping your audience would feel that live action might not deliver?

Where live action might capture immediacy, stop motion allows for a surreal, dreamlike quality. It lets me exaggerate, distort, and abstract in ways that feel more spiritually resonant, like entering a myth instead of just watching it. I want the audience to feel like they are holding time in their hands, witnessing something sacred unfold slowly, purposefully. That meditative pace invites reflection. It asks the viewer to sit with the story, not just consume it.

More than anything, I wanted to build a world where Yoruba cosmology doesn’t have to conform to Western cinematic norms. Instead, it breathes in its own rhythm, one that connects us to our ancestors while pulling those stories into the present. I always say, as long as I can see it, I can build it. That’s my gift—I see.

You’ve spoken about building your sets from scratch, on your dining table, using a phone, and little more than willpower. How do you navigate the tension between artistic ambition and the material limitations of being a solo creator in an industry that doesn’t yet “see” animation?

I honestly don’t see limitations except financial ones. There’s no world I’ve envisioned that I haven’t found a way to build. I create everything; puppets, costumes, sets, and props by hand. The ambition is there. The means? That’s where it gets tricky.

But even in that, I find purpose. Labour has universal appeal. People may not love your work immediately, but once they understand what it took, they respect your dedication. The Nigerian industry may not fully “see” animation yet, but the work itself speaks. You just have to keep showing up.

Stop motion is often associated with whimsy and childhood in the West, but your film felt rooted in ritual, ancestry, and even spiritual weight. How did you think about tone when animating Yoruba mythology, and what visual references or traditions shaped your aesthetic?

I don’t always “think” my way through stories; I receive them. With ‘Pa Aromire,’ I was meditating in my living room and suddenly saw a farmland. That’s how it begins: like a zip folder dropping into my spirit. I don’t know the full contents until I start unpacking it, day by day. It’s divine.

When I started animating, I didn’t even have the ending written. But I was guided, and eventually it revealed itself. I’ve designed over 300 film sets: music videos, commercials, and spaceship interiors. I know how to create worlds. But with this, there was a different kind of help. Spiritual. Some elements I included later turned out to be historically accurate and I had no prior knowledge of them.

This work pulls from ritual and vision. I’m a deeply visual person, and when I “see,” I move. ‘Pa Aromire’ came to me like that. I just followed.

Animation, even more so than film, requires obsessive attention to detail. How do you keep from burning out or over-perfecting when you’re so close to every frame? And do you have a personal marker for when something is “done”?

First, my life is structured around my work. I don’t go out. I work from home. I’ve built a studio into my living space. Except for Sundays when I go to church, I’m always creating. So the idea of burning out doesn’t really apply; it’s all joy to me. I love it.

I avoid deadlines and film festival pressures. If I miss a submission, I miss it. I don’t let that determine my pace. But I do check myself when I start to over-perfect. I ask: does this serve the story? What happens if I leave it as is? What’s the simplest, truest version? That keeps me grounded.

Many in Nollywood are chasing scale, cinemas, Netflix, and AMVCAs, but your process embraces the handmade, the small, and the quiet. Is this a personal resistance to the speed of mainstream film production, or is it just who you’ve always been as an artist?

I’ve tasted scale. I’ve worked on massive sets with huge artists. But what I do now feels like purpose. There’s fulfilment in every step. It’s sacred. It’s slow. But it’s mine.

And the beauty is, even from this small space, the work travels. ‘Pa Aromire’ became the first animated film to win an AMVCA. We took ‘The Travails of Ajadi’ to the biggest animation festival in the world: Annecy. So it’s not about resisting scale. It’s about staying aligned. From there, everything else follows.

What was the most emotionally difficult scene to animate in ‘Pa Aromire,’ and what made it hard technically, narratively, or spiritually?

The Igi Ogbon scene. That tree of wisdom. The idea didn’t even exist when I started animating; it came at the very end. I had to build custom rigs to rotate the tree on its own axis and in orbit while the camera moved in and tracked vertically. All of that, simultaneously.

The final shot looked like the tree was charging at you. I loved it. But when people watched it, most didn’t notice. Only a few asked how I achieved it. But it meant a lot to me, and the film was nominated for Best Cinematography at the Toronto International Nollywood Film Festival (TINFF), so someone did see it. That shot was my heart on screen.

If a young Nigerian animator told you they wanted to enter the world of stop motion tomorrow, what would you tell them to protect, and what would you tell them to let go of?

Protect your sense of purpose. Protect your vision. You’ve been equipped for something specific; don’t lose sight of that. Let go of your need for approval. I used to post behind-the-scenes clips on Instagram, thinking people would appreciate the effort, buzz me, and cheer me on. They didn’t. Especially not industry people. No one cares until you win awards.

So post what you want. Stay consistent. And when the time comes, the right people will find the work. Low engagement is not proof of low value. Be who you’re meant to be. The “big things” are just extras. Your purpose is the main event.