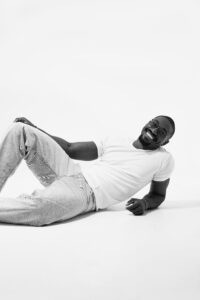

VINTANO HOTEL, LEKKI, LAGOS STATE, NIGERIA. For years, Moses Babatope has been a central figure in how Nigerian films reach audiences. In nearly 25 years of work in distribution and exhibition, he has helped bring Nollywood to the big screen at home and abroad, set box office records, and backed some of the industry’s most successful titles.

Today, he stands as Nollywood’s highest-grossing executive producer and one of the industry’s most experienced distribution executives, with two billion-naira blockbusters under his belt.

Yet, in an era when some industry voices claim “cinema is dead”, Babatope is doubling down, planning to open more screens, not fewer.

“It’s our culture of experiencing things together,” he told The Spotlight host Banke Fashakin. “That communal culture is what makes cinema special here. We have a duty to preserve it.”

From London Nights to Lagos Premieres

Babatope’s entry into cinema was hardly preordained. Raised in a strict Deeper Life household where television was banned, his earliest brushes with film came through his younger brother, Babajide, who would sneak next door to watch movies and drag him along. Years later, while working at Odeon Cinemas in London, it was Babajide again who urged him to start showing Nollywood titles.

In the mid-2000s, Babatope and his partners began experimenting with late-night Nollywood screenings in the UK. “We knew the films weren’t the highest quality technically,” he said, “but we saw an audience already buying VCDs in places like Peckham and Brixton. We just asked, ‘why not in cinemas?’”

Those late-night screenings became a phenomenon, sparking a UK premiere culture that soon returned to Nigeria with Babatope and others. Today’s red carpet openings and box office runs trace their lineage to that experiment.

Nile Media Entertainment Group and the “Cinema-for-All” Mandate

In 2024, Babatope left Filmhouse Group to launch Nile Media Entertainment Group, where his focus is expanding cinema access in two directions: high-end luxury experiences for affluent audiences and affordable, communal screenings for underserved communities.

“There is no Nollywood industry without that segment,” he said of lower-income viewers. “They are the real fans. They validate our stars. We just haven’t given them enough access. And when we have, it’s been too expensive.”

Babatope admits this approach isn’t immediately profitable. “It’s a long-term play,” he explained, pointing to its potential for social cohesion, education, and cultural exchange. “Look at India. Village cinemas are still thriving. It’s not too late for us.”

For Nile, this also means exploring new territories, from the Nigerian diaspora to countries like Finland, Saudi Arabia, and even China, where he says African cinema remains undiscovered. “If the South Koreans can do it, Nollywood can,” he said.

Addressing the Cracks in the System

But Babatope is not blind to the industry’s challenges—chief among them, tensions over fairness between producers, distributors, and exhibitors. Some accuse cinemas of favouring their own titles, shutting out independent producers.

“I’m not going to say it doesn’t happen,” Babatope acknowledged. “Sometimes it’s just giving your own film the best chance because you’ve invested heavily in it. But there’s still a level playing field for films audiences want to see.”

He argues that success requires more than finishing a film: it demands marketing resources and an end-to-end plan. “You can’t compete with people like Funke Akindele or Toyin Abraham without committing serious resources. This is not an industry where someone’s going to save you.”

Moses Babatope: A Relentless Optimist

For Babatope, the future of Nollywood cinema is not about nostalgia for a golden age but about building new pathways; whether through luxury hotel cinemas or pop-up screens in remote towns.

“We’ve been content with what we think cinema is,” he said. “For me, as long as it’s communal, immersive, and offers something you can’t get at home, it’s cinema. The question is, “How do we scale that?”

It’s the same restless curiosity that has defined his career from those first late-night screenings in London. And in a business where others are slowing down, Moses Babatope is still moving forward—screen by screen.