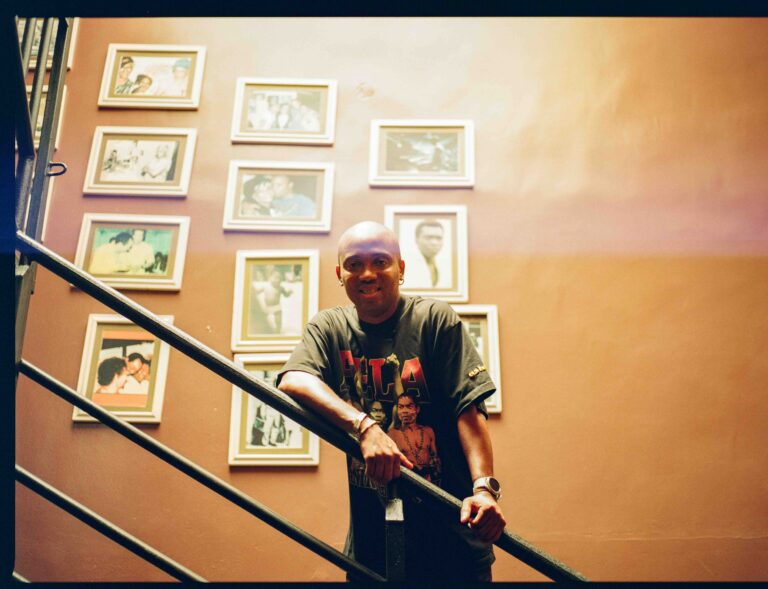

Bunmi Ajakaiye’s earliest memories are dotted with VHS tapes courtesy of her older sisters. She grew up watching ‘The Sound of Music’, ‘Rocky’, ‘No Retreat, No Surrender’ and the Nollywood classics, including Tunde Kelani’s ‘Oleku’ and Alhaji Ajileye ‘Koto Orun’, amongst others. She describes her sisters’ film palette as “adventurous” because they welcome all genres into their home.

Many who chose the filmmaker path owe a title for leading them to their destiny but for Ajakaiye, she is clueless as to what movie did it for her. What she vividly remembers is the feeling that clothed her when she watched those films, the feeling of communality. “Anytime we gathered to watch movies, my whole family were together in the same room, at the same time, focusing and enjoying the same thing. For a house full of many siblings and cousins who were always off doing their thing, it felt like the one time we were truly together,” she recounts warmly.

For 90 to 120 minutes, Bunmi Ajakaiye sat in that sense of community, a kinship brooding between people who were much older. There was no Bunmi, no aunty, no grandpa, just an audience who enjoyed what was playing on the screen. Thus, she decided to chase this communalism and bring it to people through her work. “I thought that if this ‘cassette of a thing’ was this powerful as to assemble people in one place and bolster such a sense of togetherness, I wanted to do this for other people too. I wanted to make this exact same impact,” she states.

Decades have passed since Ajakaiye encountered that feeling and she has kept her vow. She co-wrote the smash hit ‘Sugar Rush’ and the crime thriller ‘Black Book’. She also has writing credits on ‘Skinny Girl in Transit’, ‘Up North’, ‘Selina’ and her latest, ‘Heart on the Line’.

In this Off Camera feature, she sits with Nollywire to discuss the state of writers in the industry, their challenges, and her desire for writers.

There’s a constant debate about the quality of writing in Nollywood. Do you think the writing is the problem, or are there deeper systemic issues at play?

I think Nollywood is like any other industry; there are people who are well seasoned and there are those who are cutting their teeth and there are those in between. Truly gifted writers exist in Nollywood and not just a handful. The criteria for engaging them and giving them adequate time to create something truly special may be something the clients out there may not be ready to give. Hence, engaging the nearest writer they can find while unfortunately expecting the level of excellence that a ten- or twenty-year veteran (or so) can give.

You’ve written and directed across genres. When you’re wearing the writer’s hat, what are some challenges you face in getting your voice and intention preserved through to the final product?

One of the most challenging things for any filmmaker, writer or not, is making sure that intention matches output. A lot of things get lost in translation during execution even when you are right there. You have to fight for your story if everyone isn’t on board with your vision. Every single unit has to be one hundred percent aligned with the overall vision and they must commit to it.

However, we are dealing with human beings, not machinery. Some things will just not get done exactly as you imagined. There are strategies to deal with this; having full creative control is one of them but full creative control is most achievable if you are also bankrolling the project. An executive producer may have other ideas and one may painfully have to compromise.

Let’s talk about pay. What does the current compensation structure for screenwriters in Nollywood say about how the industry values (or undervalues) writers?

We as an industry of filmmakers exist in the Nigerian ecosystem, one where regulation in the broader sense is still a bit challenging even at higher levels. For the fact that we exist in such an unregulated society already, Nollywood is not immune to the pitfalls of lack of structure. Being a largely independent industry, everyone negotiates their own worth. It’s a free market to boot. Laws of demand and supply are at play, especially with youtube seemingly leading the charge now. A writer states her or his worth and hopefully matches with a client who sees the value and is happy to pay.

Beyond the money, what kind of treatment do writers typically get on Nollywood sets or productions and how has that shaped how you advocate for or approach your own teams?

A writer’s job typically ends at the point of submission. If the production requires them to get involved during production or make multiple adjustments according to the notes from top production members, then that is a separate conversation. The script is now handed over to the director to interpret to the best of her or his ability and to avoid disrupting the creative process, a professional writer knows his position and maintains it.

Has there ever been a time when you felt disrespected as a writer on a project, and what did that moment teach you about the ecosystem?

Fortunately, that has never been the case. I know the limits of my job as a writer and respect everyone in the value chain. Another thing that makes that an experience I hardly face is representation; I have multiple teams and agencies that look out for my interest and charge me quite heavily for it but it’s a fair price to pay.

Do you think our current structure allows writers to grow in the industry, going from beginner to mid-level to showrunner, for example, or are we still operating in silos?

We are in amazing times now in this industry where teaching materials and resources for improvement are literally at our fingertips. Back then, you’d have to find a school, hope and pray they have actually good writing teachers and then absorb the knowledge in trickles. Now, almost everything you need to build capacity is right there on the internet for those who believe in continuous learning and improvement of their craft.

If you had the power to radically shift how writers are treated in Nollywood, what are three changes you’d implement immediately?

Visibility. People absolutely do not care about who wrote what, at least not in these parts. It’s ironic because it literally starts with us but even the media hardly reports on us. I’d improve visibility of writers on projects and turn the spotlight on them. I would try to negotiate decent royalty payments if such a thing becomes the norm in nollywood as a whole. I’d also try to connect our writers with our peers globally for an exchange of ideas, strategies and systems, building global communities from our own home which could position us for collaborations on a global scale.

What genre feels most like home for you when you’re writing and is there one you haven’t tackled yet that’s calling your name?

I am very partial to stories that make people feel good, hopeful, joyful and secure even if it’s for a few hours. I respect all genres and can function in almost all but my underlying motivation is still to bring people together and strengthen the sense of community through film. Any genre that can do that, which is basically all, is right up my alley.

A genre or should I say sub-genre, I am really getting stuck into is social impact, stories that carry a social impact. I’ve known for a long time that what I do has more than the power to entertain; we can change the world by turning the attention of people to issues affecting our social development. Any movie where I have had creative control, I’ve inserted a social impact message; for instance, my short film ‘Fractured’ on YouTube highlights gender inequality as it intersects with sexual and reproductive health. I also highlighted period poverty for underprivileged girls in my film who lived at number 6 and I hope to do more of such advocacy work in the sub-genre we can term ‘film for advocacy’.