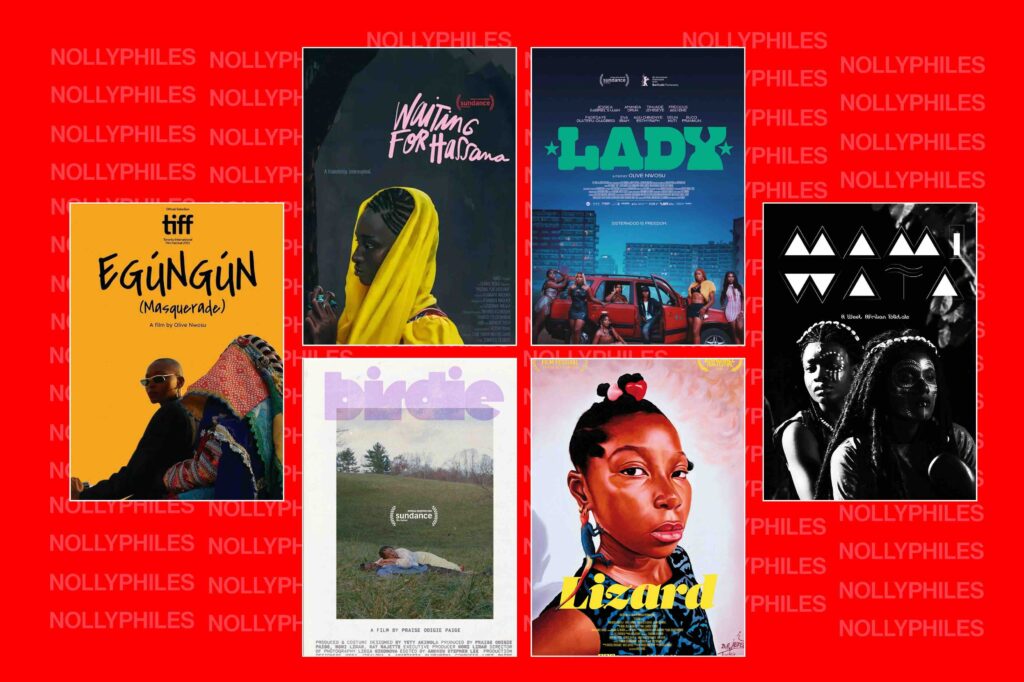

The Sundance Film Festival has become an unexpected showcase for some of the most compelling Nigerian films. From haunting folklores to intimate character studies, these films have earned their place on one of the world’s most prestigious independent film stages and they deserve a spot on your watchlist too.

Waiting for Hassana (2017)

Uzodinma Iweala’s ‘Waiting for Hassana’ marked an early turning point for Nigerian stories at Sundance. This contemplative film centres around the themes of absence, expectation, and emotional suspension. The story unfolds around the act of waiting, using stillness and restraint to explore how uncertainty shapes relationships, memory, and hope. It’s the kind of character-driven storytelling Sundance has always championed: quiet, patient, and deeply human.

‘Lizard’ (2021)

Akinola Davies Jr’s ‘Lizard’ became the first Nigerian production to win Sundance’s Short Film Grand Jury Prize, marking a historic milestone for Nigerian cinema. 8-year-old Juwon possesses some ‘strange’ power and is kicked out of Sunday school and discovers the dark, corrupt, and criminal underbelly of a Lagos mega-church. The film features a stellar cast, like Pamilerin Ayodeji, Charles Etubiebi, Osayi Uzamere and a host of others. As a short film, it delivers a tense, beautifully crafted story that lingers long after the credits roll, a significant breakthrough for Nigerian short filmmaking on the global stage.

‘Egúngún’ (2022)

Olive Nwosu’s ‘Egúngún’ draws inspiration from Yoruba masquerade traditions to explore themes of identity, cultural memory, and spiritual inheritance. Salewa (Shelia Chukwulozie) is a young woman who returns to Lagos seeking healing. The film is deeply rooted in Nigerian culture yet speaks to universal questions of belonging and selfhood. The cast includes Teniola Aladese, Loveth Onyemaobi, and Angel Peters. Its inclusion at Sundance reflects the festival’s growing recognition of African films that honour local traditions while engaging ideas that resonate across borders.

‘Mami Wata’ (2023)

C.J. “Fiery” Obasi’s ‘Mami Wata’ won the World Cinema Dramatic Special Jury Award for Cinematography, and it’s immediately clear why. Shot in black-and-white, the film tells the story of a community that places its faith in a powerful water deity believed to protect and guide them. When tragedy strikes and doubts begin to surface, the village’s spiritual order is thrown into crisis, forcing its leaders and followers to confront the fragile boundary between belief, authority, and rebellion. The film’s visual language positions it as one of the most visually ambitious Nigerian films to achieve global recognition. The film stars Uzoamaka Power, Evelyne Ily Juhen, Emeka Amakeze, Rita Edochie, and Kelechi Udegbe.

‘Lady’ (2026)

Olive Nwosu returned to Sundance with ‘Lady’, which premiered in the World Cinema Dramatic Competition, one of the festival’s most competitive categories. The film follows a Nigerian woman navigating questions of identity, autonomy, and self-definition within a society shaped by expectation and restraint. Set against an intimate social backdrop, the film examines the tensions between personal desire and public duty, exploring how women negotiate power, visibility, and survival in spaces that are not designed for them. Jessica Gabriel’s Ujah, Amanda Oruh, Tinuade Jemiseye, Precious Agu Eke, and others are among the cast members.

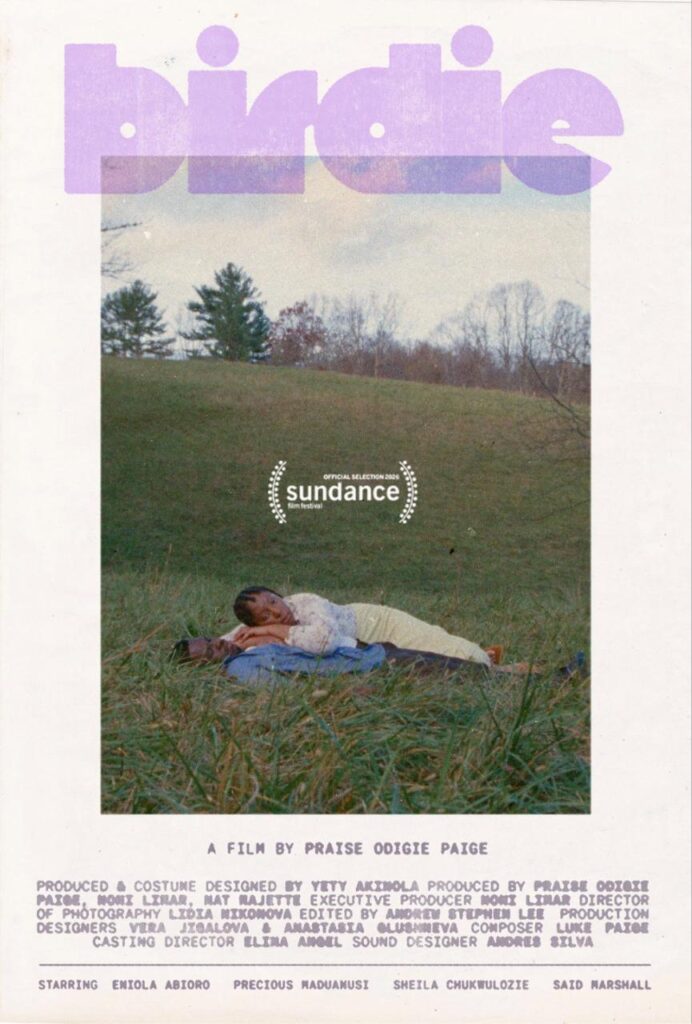

‘Birdie’ (2026)

‘Birdie’, directed by Praise Odigie Paige, was selected for Sundance’s highly competitive Short Film Program in 2026 and explores the themes of intimacy, emotional fragility, and the unspoken weight of human connection. Set in the 1970s, a 16-year-old Nigerian refugee tries to keep her family together when a newcomer draws her sister away. Told through a character-focused lens, the film follows a fleeting but transformative encounter that forces its characters to confront vulnerability, longing, and the need to be seen. The cast includes Eniola Abioro, Precious Maduanusi, Sheila Chukwulozie and Said Marshall.

These films represent more than individual achievements; they signal a shift in how our stories are being told on the global stage. From Iweala’s introspective restraint to Obasi’s visual grandeur, Nigerian filmmakers are claiming space at Sundance not as outsiders but as essential voices shaping contemporary cinema.

Whether rooted in folklore, cultural memory, or the quiet complexities of everyday life, these films prove that Nigerian storytelling belongs in any conversation about the future of independent film. They’re not just worth watching; they’re impossible to ignore.