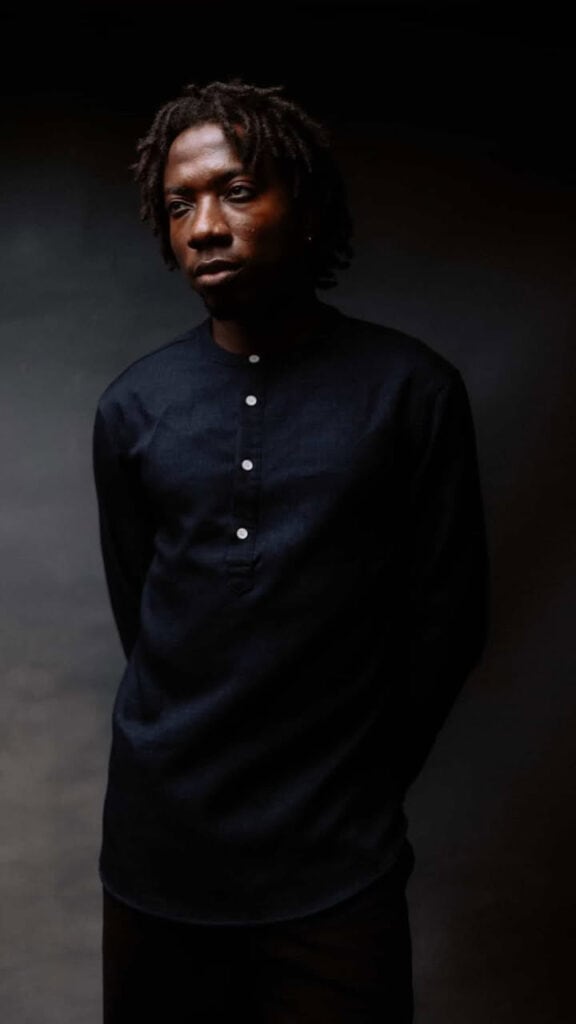

“You are a romantic,” I tell Dika Ofoma, forty minutes into an hour call. Ofoma is an emerging filmmaker known in the indie space. His short films ‘A Japa Tale,’ ‘A Quiet Monday,’ and the S16 favourite ‘God’s Wife’ have all received duly deserved accolades. “I think I am,” he replies, hesitation clinging to each word. But anyone who has seen the intimacy of ‘A Japa Tale’ and the quiet comfortability the characters share will tell you his reply needs no hesitation; Dika Ofoma is interested in romance.

Ofoma’s choice to explore romance in frames is his way of capturing what is true. “We are people who crave. We want to be known by someone, we want to be seen by someone,” he states. A true romantic, he finds the creation story endearing. “Even in the Bible, the way creation is described, God takes the rib of a man to make a woman. There’s something very romantic about that, about the idea that someone is made from you or that a part of you exists in someone else. I think it’s beautiful.”

Although he is very intrigued by the subject of love, Ofoma strays where the traditional romantic excels: happy endings. He cites Marianne and Connel’s love story from Sally Rooney’s ‘Normal People’ as his favourite love story—a story void of the conventional happy ending. “I don’t think I’ve been affected by anything in the way that I was affected by ‘Normal People,'” he tells me. “I think what draws me in is just observing people, watching them be in love. Seeing how they change, how they stay together, how their lives get messy, and how that messiness shapes the relationship. “That’s something I found really powerful in ‘Normal People,'” he adds.

Albeit shorter in its minutes, ‘A Japa Tale’ does the same in quick glances. ‘Normal people’ and ‘A Japa Tale’ share similarities in the sense that they are romantic stories without happy endings and grand gestures, both fabrics of the romance genre. “When we think of romance, we often think about grand gestures, being flown out, a fancy dinner, a sparkly dress, and an expensive ring. And that’s all great. But I think the most beautiful thing about romance is how much people are willing to be vulnerable and open.”

Often accused of being drawn to sad stories, the filmmaker pushes back, “If you look at the world as critically as possible, you’ll see that life isn’t always happy.” This acute observation informs his approach to storytelling. Despite being painfully aware of the sorrows life brings, he tries to strike a balance. “I try to honour the joyful moments too. But if there’s one story of mine that’s completely devoid of any happy momentum, it might be ‘God’s Wife.’ Still, even in that, if you look closely, there are glimpses of something more.” His work aims to capture the full emotional spectrum of life.

Whether romantic or sad, Dika Ofoma’s stories are embedded with messages. In ‘A Japa Tale’ he addresses the complexities of relationships, pointing us to the other ills that can ruin a relationship aside the infamous infidelity. ‘A Quiet Monday’ speaks to the sit-down Mondays enforced by the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB). ‘God’s Wife’ calls out the contemptuous and patriarchal widowhood practices in Eastern Nigeria.

His work can easily be shelved in the advocacy department and he does not mind, as he believes storytelling and advocacy are intertwined. “Storytelling is about expressing and saying something about the world around you. And once you’re saying something, that often means you’re also advocating for or speaking against something, even if it’s not intentional,” he explains.

He goes on to solidify his point. “Even in stories about romance and love, there’s always a bit of advocacy. You’re not just telling a love story; you’re also pointing out that something might be wrong with the way we, as a society, interact with certain kinds of love.” In his most recent work, ‘Something Sweet’ from the Zikoko Life film anthology, he explores how society responds to love between people of different age groups. He posits that society often pushes back against certain kinds of relationships for instance, intergenerational ones. Thus, when a romance is crafted around that dynamic, the storyteller ends up in the advocacy lane regardless of intent.

This nature of storytelling makes room for propaganda but Ofoma is far from a propagandist. With his films, he is not telling but showing, presenting you with the facts and hoping you arrive at a conclusion. He adduces ‘A Quiet Monday’ as a perfect encapsulation of his thought on the subject. “It is very observational. I try to stay away from making it look polished or pretty because I want you to really see it. And the truth is, sometimes we don’t realise how wrong something is until we see it reflected back to us.”

Dika Ofoma’s criterion collection are films with heavy themes that make one wonder if he places value on entertainment. Surprisingly, the filmmaker cares about entertaining his audience: “I think people come to film to have a good time.” He continues, “Even if you have a message, it is important to keep the audience with you as you deliver your message.” Entertainment is a tenet of his artistry; even when the story is void of witty dialogue and physical comedy, he wants you to find the images pleasing. And the opportunity to do this has been awarded to him.

In June, he announced that his debut feature-length film, ‘Kachifo,’ made the Locarno Open Doors selection with Blessing Uzzi tapped as the producer. Since 2003 Locarno doors has championed filmmaking in regions where independent cinema is challenging by providing an avenue for collaboration across countries and continents. The filmmaker had prior knowledge about Locarno Open Doors but he properly interacted with the institution during the S16 festival, where he joined a workshop and was asked to submit a dossier for his film.

He wasn’t ardent about pursuing it; there were days he felt uninspired but this lack of enthusiasm was mostly sponsored by that syndrome every creative is acquainted with: imposter syndrome. “I felt like my CV wasn’t strong enough. It was one of those things where I thought, oh yeah, I could apply next year; I really wasn’t thinking too hard about applying,” he admits. A week to the deadline, he felt the gnawing urge to apply; he did and the rest, they say, is history.

Teased as a reincarnation romance, Ofoma says ‘Kachifo’ embodies who he is as a filmmaker and the kind of stories he wants to tell. Oblivious to him, this is the smoking gun that seals his enthralment with romance. Though somewhat a contrarian, at his core, Dika Ofoma is a romantic.